The advent of autonomous trucks is being touted as a win-win across the board. Experts claim driverless trucks will be more efficient, as the artificial intelligence (AI) operating big rigs can spend unlimited hours on the road. And many claim that the roads will be safer as autonomous technology eliminates or significantly reduces semi-truck crashes — most often attributed to human errors. Autonomous 18-wheeler trucks could mean no more truck drivers hitting the road on too little sleep, getting distracted while driving, or making mistakes or poor decisions that lead to devastating crashes.

But are these AT safety claims true? In 2021, Federal regulators estimated that self-driving “cars and trucks under testing or being deployed commercially will be involved in at least 200 crashes annually over the next three years.” That isn’t exactly a ringing endorsement for the launch of the driving technology behind autonomous vehicles … and the implications are even more serious considering that some of these will be large semi-truck accidents.

A few commercial truck AT crashes are already on the books:

May 2022: A Class 8 Waymo Via truck operating in autonomous mode with a human safety operator behind the wheel was hauling a trailer northbound on Interstate 45 toward Dallas, Texas. At 3:11 p.m., just outside Ennis, the modified Peterbilt was traveling in the far right lane when a passing truck and trailer combo entered its lane. Waymo’s truck and trailer were pushed off the roadway, and the Waymo safety operator was taken to a hospital for moderate injuries.

April 2023: A driver-supervised autonomous truck from TuSimple took an unintended sharp left turn across a lane of westbound traffic on Interstate I-10 in Arizona and struck a concrete barrier. The safety driver tried to counter steer the truck, which followed a computer-generated command that was several minutes old. TuSimple initially said the incident was driver error.

Researchers at Carnegie Mellon University said it was the autonomous-driving system that turned the wheel and that blaming the entire accident on human error is misleading. To read a comprehensive review of the crash, visit The Wall Street Journal’s August 1, 2022 article entitled “Self-Driving Truck Accident Draws Attention to Safety at TuSimple”. TuSimple later it acknowledged its computer system and the safety driver both bore responsibility.

Autonomous Trucks Defined

While terminology is sometimes used interchangeably, the U.S. Department of Transportation defines an Automated Vehicle as equipped with “any form of driving automation.” Considering that standard vehicle safety systems such as warnings and alerts are deemed automation, the more common understanding of self-driving trucks is that they require little to no human involvement to operate.

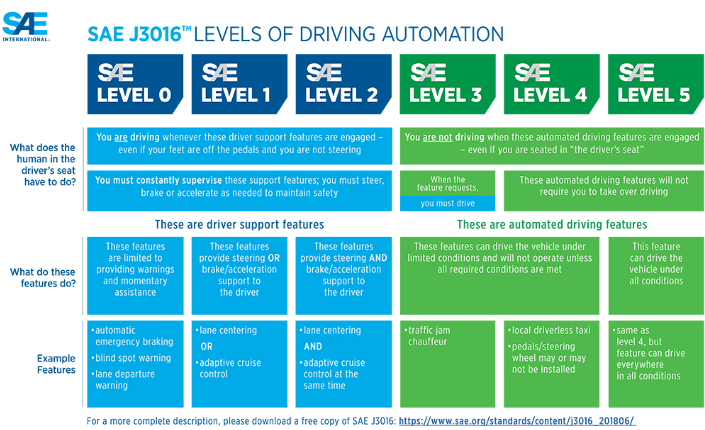

Five levels of automation are recognized by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA); ATs will likely fall under one of the last few levels (conditional automation (level 3), high automation (level 4), full automation (level 5)) if all testing goes according to plan.

Introducing truck automation on open roads continues to be a gradual process. One company started operating their ATs in port facilities, as terminals are not open to the public and require low speeds, which offers a closed, safe environment.

Other companies have been testing on interstate highways since 2018 with a California to Florida trip completed by an AT and its human passenger, while a cargo route between Texas and California has been operating since 2017. Michigan has been testing ATs since 2017. Locally, beer was delivered from Fort Collins to Colorado Springs by a supervised AT as early as 2016.

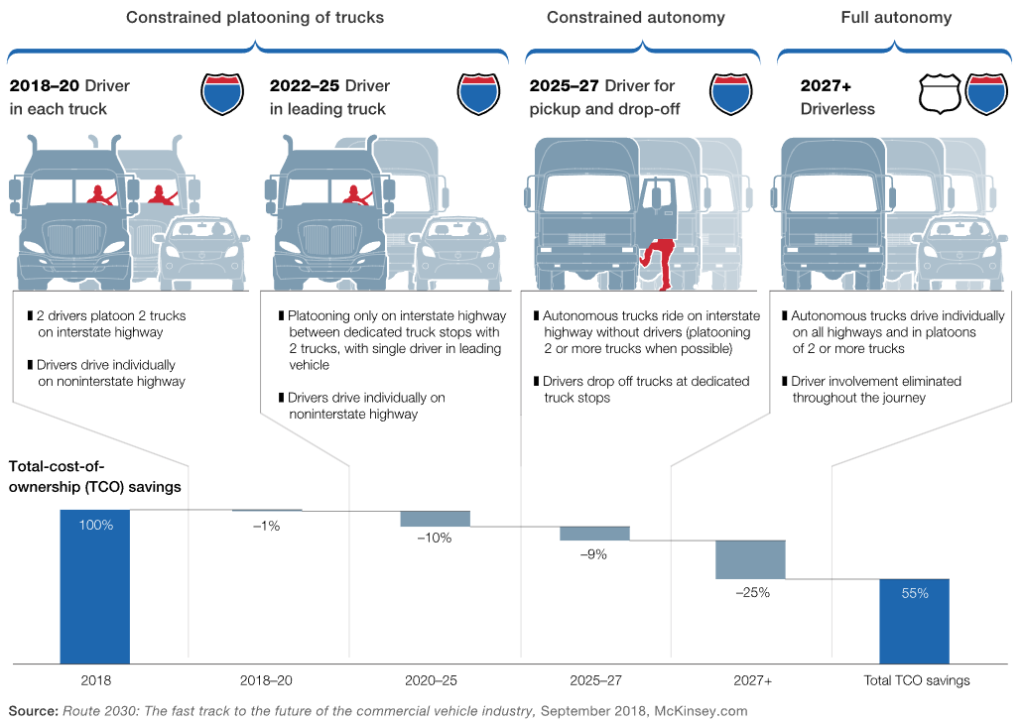

Some analysts say “widespread adoption of the technology is three to five years away,” while the actual implementation of driverless technology could take until 2030 or beyond. The rollout is envisioned as having several phases, with increasing levels of autonomy at each stage. One forecast predicts that widespread AT usage will consist of platoons, or convoys of trucks, connected wirelessly “to a lead truck, allowing them to operate safely much closer together and realize fuel efficiencies.”

Platoons Replace People

The platoons will eventually phase out driver involvement, reducing operating costs and saving the trucking industry between $85 billion and $125 billion annually. The obvious expense reduction is in truck driver salaries, since “driver wages and benefits account for about 45% of costs.” Other human factors such as hiring, training, coverage for sick days or PTO, and drug testing requirements would be eliminated by ATs. They would also enable carriers to use truck assets 20 hours per day rather than 11, thereby increasing efficiency and expanding capacity.

Only the largest, most well-capitalized million-dollar/billion-dollar trucking carrier corporations can implement autonomous trucks – basically phasing out its lifeblood of drivers and beating out the competition. Small, individual owner-operator carriers do not have the capital for the equipment or infrastructure to compete with long-haul ATs run by large trucking corporations, nor the routing software to manage it.

That means tens of thousands of truckers holding their Class ‘A’ CDL licenses will find themselves unemployed. And that doesn’t address the very real safety concerns of an 80,000 lb. tractor and trailer without an actual physical human driver behind the wheel.

Autonomous Truck Wrecks: Safety Concerns

- Software Malfunctions: When an autonomous truck causes an accident, a software malfunction is typically to blame. AI software, LiDAR, cameras and radar are not without glitches. The software may not recognize a potentially hazardous situation and thus does not adjust accordingly… the way a human driver would. This can lead to a potentially deadly accident.

- Hacked Technology: Autonomous trucks can be hacked, with someone remotely taking control of the vehicle via the truck’s computer system. This can turn the truck into a weapon. FBI Supervisory Special Agent David Smith, who is the transportation program manager within the federal agency’s cyber division, said the “transport sector can be targeted by hacktivists, criminals, insiders, spies, terrorists and countries engaged in warfare.”

- Locational Hazards: Anything can happen on a highway: unanticipated roadway conditions such as ice, a vehicle suddenly stopping in the roadway, or large animal wandering onto the road. Combine any of these scenarios with the high rate of speeds autonomous trucks typically travel at while operating on an open highway and the consequences can be deadly. And with inclement weather comes dirt, mud, salt, and other environmental factors that literally block or interfere with the AI sensors and monitoring equipment, which is why most of the current AI testing is done in warmer weather climates.

- No Emergency Signals: The AT industry has pushed for a “relatively obscure” five-year exemption to “replace ground-based emergency triangles and flares that warn motorists of a stopped truck with cab-mounted electric lights instead. They also requested that the lights be exempt from a requirement that they be steady-burning.” This appeal stems from the fact that level 4 and level 5 vehicles are driverless, so there is no human aboard to jump out of the cab and place the warning equipment around the truck.

- No Triage For On-Road Emergencies: According to the NHTSA’s Critical Reasons for Crashes Investigated in the National Motor Vehicle Crash Causation Survey, tire-related (blowouts, flat tires) crashes topped the list. Self-driving truck companies have tested the scenario, claiming that their trucks handle a blowout “better than the average human driver”. In an emergent situation, the truck supposedly stays under control in its lane and comes to a stop. However, the unmanned big rig now must navigate getting onto the shoulder (if there is one), potentially in heavy or fast-moving traffic, only to be disabled on the side of the road awaiting a tire change by a human. And during that whole time the truck idles on the side of the road, no safety flares/triangles or other emergency signals give warning to the breakdown.

- No Oversight: Self-driving trucks are still only regulated at the state level. This means, among other things, there are no federal regulations to help ensure driverless trucks are properly maintained.

Autonomous Trucks: Not Ready for Primetime

Autonomous trucks strip away the human errors caused by fatigue, distraction, or carelessness; yet, they can’t replicate the complex decision-making abilities of a human driver when facing critical emergent situations. Nor can an AT change its own tire or place out emergency signals as required by law.

ATs can’t perform the daily physical inspection of the commercial motor vehicle (brake systems, fuel systems, frames, wheels, steering and suspension systems) from outside the cab. An AT can’t look under the hood, and it can’t assess the outer framework of the semi. Add in the fact that ATs are susceptible to failures, hacking, and glitches like any other technology… and the splashy new driving mode doesn’t seem ready for primetime.

The safest option seems to be a compromise of allowing level four and five ATs, but requiring an in-cab “operator” with their full CDL who can manage the truck in an emergency as needed. In May 2023, California lawmakers voted to require “safety drivers” in self-driving trucks, while the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Association (FMCSA) bats around the idea of having human “remote assistants” to monitor the truck and “facilitate trip continuation.”

Even some of the AT companies are hedging their bets: Don Burnette, CEO of AT startup Kodiak Robotics Inc., said his firm is leaving safety drivers in the cab until he can confirm that his trucks operate more safely than an attentive human driver.

We agree with the lawmakers requiring a human “assistant” if putting ATs on the road. Putting a 10,000 pound plus vehicle on auto-pilot seems unnecessarily dangerous, until the trucking industry works out the kinks. 200 crashes annually over the next few years is not a promising estimate, and it begs the question: in the event of an accident, who would be held responsible – the manufacturer of the autonomous technology or the owner of the truck? Let’s do away with these type of quandaries by keeping qualified CDL drivers at the wheel.

Safety on the road is the only metric that matters as newer technologies take hold. The big boys in the trucking industry (Knight-Swift, Xpress, FedEx, J.B. Hunt, Schneider, Old Dominion, etc.) should spend the money to have safety redundancies (AT and a driver) for the foreseeable future or take full responsibility for the crashes that occur.